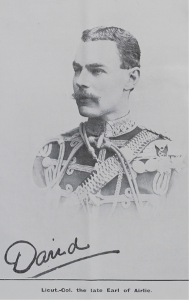

Lieutenant-Colonel the late Earl of Airlie

Lieutenant-Colonel the late Earl of Airlie

David Stanley William Ogilvy, the eighth Earl of Airlie, passed into the Army on the 8th June 1874 from Sandhurst. He was gazetted sub-Lieutenant in the 1st Foot, The Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment). On the 28th August 1874 he was transferred to the Scots Fusilier Guards, and later, on the 3rd May 1876, to the Tenth. This last transfer was afterwards anti-dated to the 3rd June 1875, from which date he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant.

He joined the Regiment at Muttra, in October 1876, accompanied it to Rawal Pindi in November 1877, and marched with the Headquarters to Afghanistan, forming part of the Peshawar Valley Field Force, in the campaign 1878-79. He was present on the 21st November 1878, at the assault and taking of Ali Masjid, and took part in several minor engagements with the enemy. On the conclusion of the first phase of the war, he returned with the Regiment to Rawal Pindi, participating in all the privations and horrors of what was subsequently known as “the death March”.

On the 21st October 1882 he was appointed Adjutant, and held the appointment until 17th February 1885, having in the meantime been given his troop on the 18th February 1884.

He preceded the Regiment by ten days when it left Lucknow for home on the 27th January 1884, and in consequence was not present at the battle of El Teb. He was in Paris when a telegraphic message, sent to him by his sister, the Lady Griselda Ogilvy, gave him the first intimation that the Regiemtn had been diverted from the homeward journey, and ordered to Suakin in the Red Sea, to form part of what was styled the Tolkar Relief Force. The only possible means of getting to Suakin expeditiously was by chartering a steamship himself, and to these means the Earl of Airlie did not hesitate to resort. A Wilson liner was secured and in this he, the solitary passenger, sailed from Marseilles. The crew o this vessel subsequently recounted graphically their passenger’s incessant efforts to induce the engineering staff of the ship to accelerate the speed, and his feverish impatience, right up to the minute moorings were taken in Tinketat harbour. This was effected on the evening of the 2nd March, and the world did not hold a more disappointed man than Lord Airlie, when he learned that the battle had been fought two days earlier. There was a small party of the Regiment at Trinketat, with whom he could have remained, but such was his eagerness to get up with the Regiment, that, taking one of the men with him, he proceeded that same evening, in the gloom of the desert, to Fort Baker, which was a base, and then early the next morning to the village of Dubbeh, where the Regiment was. It was one of the chief regrets of Lord Airlie’s life that he had missed those three preceding days. He took part in the battle of Tamaai, and in the reconnaissance of Tamanieb, also on the advance of the Sinkat Road, when the villages of the Dervish Chief, Osman Digna, were destroyed.

On arrival of the Regiment at Shornecliffe he continued as Adjutant, but for only five months. The call of the Soudan again appealed to him, and on the 2nd September he was again obeying those soldierly instincts that pervaded his whole being, and was serving on the Staff of General Sir Herbert Stewart, Commanding the Cavalry of the Nile Expeditionary Force. Very soon he was appointed Brigade- Major of that Force and in this capacity he served until the end of the Campaign.

He was present at the important battles of Abu Klea (wounded), the famous Gubat (wounded), Where the British square was broken by the impetuous charge of the death defying Dervishes, and that intrepid soldier Colonel Fred Burnaby fell, in the reconnaissance towards Metamneh in January 1885, and the engagement at Abu Klea, during the retreat across the desert in the following month. Of this march, that great German soldier, Bismarck, declared that “every man who took part in it was a hero”. For his part in this campaign Lord Airlie was mentioned in despatches by Lord Wolseley, and given a Brevet Majority, Clasp Nile 1884-85, Order of the Medjideh.

Portraits of Lord Airlie are included in two pictures of the period, which caused sensation – one a oil painting of the incident at Gubat, at the moment when Burnaby advance from the square to oppose the foemen’s rush and met the soldier’s death he desired: in this Lord Airlie is represented as he fought that day, with one wounded arm in a sling, his wounded neck bandaged, and in his sound hand an Arab spear, the only weapon with which he as armed.

The second picture was one which formed a trenchant answer to the theories propagated by the radical and socialist communities, entitled “They toil not, neither do they spin”. In this Lord Airlie, with two other soldier peers who were fighting and undergoing all the privations of an arduous campaign, what time their detractors were disseminating sedition and discontent at home, comfortably battened on the funds extracted from their foolish followers.

On the cessation of fighting in the Soudan lord Airlie rejoined the Regiment and did duty with it until July 1899, when he took over the Adjutancy of the Hampshire Yeomanry, and during his four years in that appointment, by his practical and zealous service, brought that body to a state of perfection rarely attained by troops subject to conditions of training in Auxiliary Cavalry. Rejoining the Regiment at Cahir in 1893, he accompanied it on change of station to Ballincollig, , proceeding to Cork in command of the attachment there. On the march of the Regiment to Newbridge in May 1895, he, with his detachment, rejoined Headquarters there and served until January 1897, when, to the regret of all, he was transferred to the 2nd Dragoon Guards as Second-in-Command. Such is briefly the history of 21 years, 213 days of a Tenth Hussar, whose mane the Regiment is proud to have borne on its rolls, a name that will always be remembered as one which adds lustre to it, and to the Empire for which he gave up his life. This weak account of his service can only in the feeblest manner convey the effect of his influence on the Regiment. All whose privilege it was to serve with him, recognise and appreciate the immense power of good, of the personality and example of this fine soldier, for prototypes of whom we must seek among such General Gordon, Captain Hedley Vickers, and other God-fearing heroes, who have set up models which will be handed down to posterity as glorious types of the British race as long as time will last.

Although Lord Airlie, by the exigency of military service, ceased nominally to be a Tenth Hussar, we claim him as one who ever considered himself as one of the Regiment, even after his severance from it, and no doubt can be entertained that his affection for it never diminished; it was ever first in his thoughts. After a brief stay with the Bays he was again transferred to the 12th Royal Lancers as Commanding officer, a command that brought us in close touch with him in the days of the South Africa War. Many a trying march, many a hard fight did the Tenth and Lord Airlie’s Lancers engage in, side by side and on man y a stricken field did they mourn the good comrades of both regiments who had fallen. Together the Tenth and Twelfth trekked and fought until that fatal day at Diamond Hill – the 11th June 1900 – when he fell, as it surely was his wish to do, leading his regiment against the enemy. Even on that day we have the melancholy satisfaction of knowing that with this gallant Tenth Hussars, under his command, were men of his old regiment, for a party of “C” Squadron under Sergeant Lyons, charged that day with the Twelfth, and were close to Lord Airlie when he fell, shot through the heart by a Boer rifleman.

Lord Roberts, the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in South Africa, in a special order of the day mourned the loss of “that gallant soldier The Earl of Airlie”, and his words found an echo in the hearts of thousands of soldiers. Historians have published to the world the splendid acts of Lord Airlie in this war, proclaiming his right to praise for his unconventional use he made of his men on the terrible day at Mafersfontein, and for the gallantry with which he threw both himself and them into the most critical corner of the fight, and held back a flank attack through the whole of the morning. This and many similar deeds are to his credit, up to the last day, when it is recorded by a war historian that the gallant Lord Airlie, as modest and brave a soldier as ever drew sword, fell, with the characteristic remark made to a battle-drunk Sergeant “Pray, moderate your language”.

This briefly is the history of a soldier whose deeds, were they published in the manner they deserve, would fill volumes: a soldier who, it is believed, was not at first destined for the Army. But the instincts of his warrior race were far too insistent, and called him th arms, which was unquestionably his metier. How could it be otherwise? Hereditary compelled it, and nothing could suppress the fighting characteristics transmitted through many generations who have been found on every field where battles were fought for King and County. Characteristics which took that old septuagenarian Chieftain of the Ogilvy clan into the field with his three brave sons, to fight for the cause of his Monarch; and kept him in the field when many weak-hearted chief had gathered the remnants of his followers around him, and forsook the cause, when one son had been slain and another a prisoner condemned for treason awaiting his doom in Edinburgh Castle.

Nor was it only the men of the Ogilvy race who are still famous for their bravery and virtues. We have the instances of the sister of the condemned son of the house alluded to above; this lady effected the escape of her brother by exchanging clothes with him when she visited him in his condemned cell: we have the stirring poem of the “Bonny House of Airlie” perpetuating the daring of the chatelaine when the historic house was burnt by the unchivalrous Argyll. We have the story of the spectral drummer of the castle at Cortachy, and many other beautiful stories are weaved around the gallantry, the patriotism and the loyalty of the Ogilvy clan, of which the Earl of Airlie is the head, but none, even in this unpicturesque age, could excel what might be written of the Earl who was also a Tenth Hussar, to be associated with whom was an inestimable privilege, acquaintance with whom left only memories tender, beautiful and fragrant.

Copyright 2019 © Major Pillinger/Richard Pillinger. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited. www.sciweb.co.uk