Tenth was, in general, a Regiment that was very attached to the wearing of a moustache, and the feelings of the Editor of the Gazette, on hearing the rumour that the standing order to wear a moustache was imminently to be rescinded, are set out in a article that appeared in Volume 25:

Copied from The XRH Gazette No. 25 October 1913. Volume 25

A subject that was causing excitement and agitated controversy in the Home military circles, in July, was the “Army moustache”. Certain London papers predicted its doom, and the paragraph of the King’s Regulation prohibiting the shaving of the upper lip, will shortly be abolished.

The consensus of the doubtfully authoritative opinions of those who rushed into correspondence on the subject was decidedly in favour of its discontinuance. One who is described in the Daily Sketch as a “military officer” declares that “the popularity of the moustache had waned in the last ten years.

Of course the idea of the regulation may have been to save time when the troops were on the march, but I don’t think any officer begrudges the time the shaving takes now. Another idea may have been to add to the importance of young officers, who, if they were clean shaven, looked like boys, and gave the impression that they were not old enough to command the bronzed veterans in their companies.

Certainly the man who is clean shaven looks most business-like, and that is the main thing to aim at”

Col. Robert Spencer Liddell

Can any weaker arguments than those, this “military officer” propounds for the abolition of the Regulations be conceived?

Imagine the economy of time from omitting to shave the upper lip, after attending to the whiskers and beard. Estimate the impression made upon the bronzed veterans by the young officer whose moustache, except in isolated cases, could not have failed to betray his juvenescence.

“Military Officer’s” views of the desirability of business-like appearance are puerile, and unworthy of comment.

Another London paper introduces its article with the prominent headlines:

CLEAN-SHAVEN ARMY OFFICERS AND MEN OBJECT TO WEARING

MILITARY MOUSTACHE

DISLIKED BY WOMEN

Then asks pertinently “Is the military moustache to disappear?

Follows this up by the assertion that “agitation is now being made, by both officers and men in the army for the right to be clean shaven, and the abolition of the paragraph No. 1695 of the King’s Regulations” which is describes as autocratic.

The paper quotes claims to have sent representation to the War Office, where an “Official” informed him—-

Major-General the Hon. Julian Headworth George Byng C.B. M.V.O.

The paper also acknowledges the kindness of Major-Gen. Sir Alfred Turner, who gave a brief history, (unpublished) of the regulations for wearing whiskers, beards and moustaches in the Army. Also the General’s opinion “that there is among officers undoubtedly, a growing feeling against the moustache, which they are enforced to wear. He notices an increasing number of Army men who have deliberately shaved the upper lip in defiance of the regulations. The General stated that whiskers of moderate length means that men shall not have long flowing hair on their face—called, he believed, “Piccadilly Weepers” , but whiskers of the old fashioned “mutton chop design. Until the end of the eighteenth century, said Sir Alfred, officers had to be clean shaven. About 1815 the mutton-chop whiskers, popularised by the Duke of Wellington, was recognised in an Army Order.

The Editor of the paper adds — “women generally prefer the clean-shaven man – or if they confess to a liking at all for a moustache, the latter, it is specified, must be a very small one.

“I do not like moustaches at all;” said a girl of twenty, “I think a man looks much fresher and younger without one.”

Undeniably it is the press annual silly season, when space and time can be devoted to the publication of such utter drivel; it was left to a certain Chaplain, R.N. to attain the climax. He seized upon the rumour, and it is no more than a rumour still, taking no shape in officially inspired paragraph. It is possible, of course, that the W.O. may be considering the cancelation of the regulation, but experience teaches that the W.O. is not unduly precipitate: rash and catastrophic haste has no part in its procedure; many a moustache will be bleached by age while the W.O. is deciding its fate.

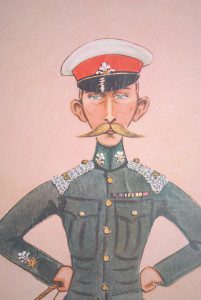

Sir Arthur Lawley K.C.S.I. G.C.I.E. K.C.M.G.

The Chaplain, R.N. is eager and impatient. For him the moustache is doomed; the razor waits for it, the lather foams. He mocks the moustache about to perish; he tells its history with contempt. The wearing of it, he says, was an “imitation of foreign adventurers who fought for the British Army in the Napoleonic Wars, and by the middle of the last century, the good old clean cut type of British face was gradually ousted by the alien moustache.”

Is it, he asks, an adornment; is it soldier-like; is it virile? Not at all. The University man, the sportsman is shaving the upper lip. “All that is wanted to make the custom as of yore, the distinguished mark of the Britisher, is its general adoption by Army Officers. If men want to grow hair on the face, why not let it grow as nature intended? A beard is, at any rate, a virile and classical appendage, and frequently aesthetic. If however, a Britisher finds it necessary to his happiness to wear the moustache alone, he might, at any rate, avoid the exotic waxing and twisting of the ends.”

The answers to Chaplain, R.N. are too obvious: they will be apparent to all Gazette readers. All through the ages Chaplain R.N. and the Chaplains who came before him, Chaplains and Bishops, Curates and Patriarchs and Archdeacons have been writing letters to the press, and have been preaching sermons and compiling books, and addressing their diocesan clergy and laity on this same note. Beard or moustache or both, trimmed or untrimmed, it is ever the clergyman who finds fault with the fashion in which the hair is worn upon lip, or chin or cheek.

You can wager that, however careful may be our instructions to the barber, Chaplain R.N. and his brethren will not be satisfied. Chaplain would allow beard to grow untouched by scissors. Once upon a time that advice was followed, and the wearers were described as prelate, as “filthy goats and bristly Saracens.”In the Elizabethan period some shaved the chin, and were asked by a divine of repute “if they would imitate heathen Turks”. No word of Dr Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, can guide our barbering towards orthodoxy, but what can be remembered is, his trim little moustache, curled upwards in a fashion that shows he at least, was not averse to “the exotic waxing and twisting up of the ends.

The Regimental July 1915 By B Richards

What does Chaplain R.N. mean when he talks of “Britisher of yore”? In days of yore were there Britishers? Were the moustached Englishmen on the hill of Hastings, the moustached, bare chinned Crusaders who rode against Saladin’s hosts, the moustached Cavaliers of Prince Rupert – were these alien or lacking in virility?

Soldiers will not be influenced in the least by the foolish discussion, or by the gross misrepresentations which imply that they are dissatisfied by the regulations that secure uniformity in the matter discussed. They will simply continue to reflect with complacency that a moustache was formerly a badge that distinguished them from civilians, who affected it hoping it would give them a soldierly air. They will hope too, that their civil friends will adopt the advice of Chaplain R.N. and so again establish the distinction between the classes, military and civil.

And Gazette readers will recall that Hussars were the first troops in the British Army, who were permitted to wear a moustache alone.

When this was published Major Pillinger was no longer serving with the Tenth, but was on leave in Torquay before setting off to Cairo. However he did continue to offer some script to the Journal ever month and this was one of his first pieces.

Copyright 2019 © Major Pillinger/Richard Pillinger. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited. www.sciweb.co.uk